The art of writing

I. Writing materials [1]

II. Writing tools [2]

III. A scribe [3]

IV. Adornment [4]

V. Covers [5]

VI. Forgery [6]

I. Writing materials

Today, paper is widely used, however, we are increasingly writing using electronic appliances. What was it like in the past?

Since man began to write, he has used various materials. Initially, there were ones that were easily accessible and whose preparation did not require the use of complicated production processes – such as stone or wood. Later, more specialized materials were used – papyrus or wax (in the form of wax slates), parchment and, finally, paper. Neither papyrus nor wax are durable materials. They easily succumb to damage, especially in unfavourable weather conditions. In the middle ages, scribes generally used parchment which was later replaced by paper.

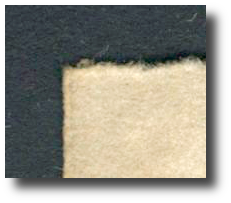

Parchment

This is specially prepared thin animal skin (most frequently calf, sheep or goat). The production process of parchment consisted of soaking, tanning and cleaning the skin, and then drying and smoothing it, and sometimes also bleaching it. As a result, a durable and strong material, resistant to damage, was obtained. Moreover, it was possible to write on both sides and a quill could pass over it easily. Its structure could be seen with the naked eye in tears or the edge of documents:

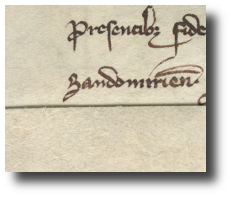

In Europe, two different types of parchment were produced. The first type, produced in northern Europe, was named “northern” or “German” (the so-called charta theutonica), made generally from calfskin and treated on both sides. The second, typical for southern Europe, from where the name of “southern” or “Italian” comes (the so-called charta italica), was more delicate and prepared for writing only on one side, therefore both sides differed significantly:

Although it was the most generally available writing material in the middle ages, it was not cheap.

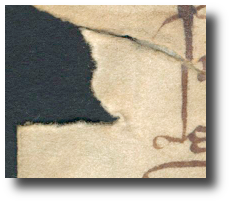

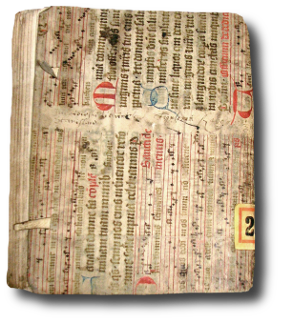

Therefore it was used sparingly, sometimes it was written on many times and even damaged fragments were used, and tears were carefully sewn.

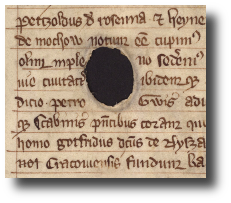

When the damage was located in the place designated for writing, the scribe simply omitted it, writing the text on both sides of the missing parchment.

The fact that the texts written by them are complete is testimony that the parchment damage existed at the moment of writing:

Paper

The production of paper began in Europe at the turn of the XIII and XIV centuries, and in Poland the first paper plants appeared in the XV century. However, paper did not immediately replace parchment. For a long time, they were used in parallel, with paper, being a less durable material, designated for writing of less importance. With time, together with the growth in writing, and finally with the increase in printing, parchment had to make way and was replaced by the cheaper paper.

The production technology of the paper in former paper plants differed from today's mass production method. The paper mass was obtained from pulp, which was a result of the process of soaking, pulping and boiling fabric. It was carried out by hand, with the use of a wire sieve, made of a network of horizontal and vertical wires (the so-called chain line and wire line), then soaked, dried, glued and smoothed. The use of a sieve meant that paper in places of contact with wire elements was lighter and thinner than in other places. This fact was used to obtain the so-called water marks, which are most visible when viewing paper under light. These were obtained with a suitably formulated wire shape mounted in the paper sieve. Thanks to this, visible graphic marks formed on paper.

The water mark identified the paper plant from which the paper came. Thanks to this, today it is possible to date and define the origin of the paper. Such obtained paper is thicker and more durable than later paper, obtained from cellulose and pulp, which began to be mass produced in the XIX century.

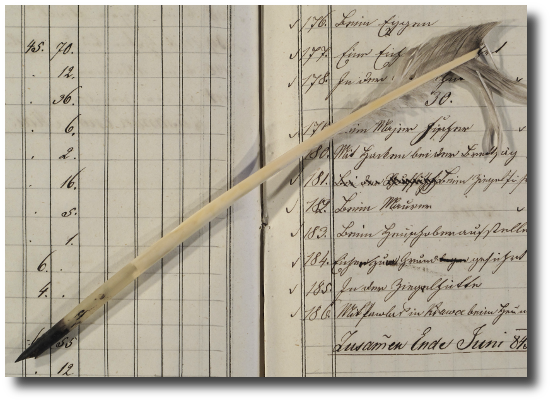

II. Writing tools

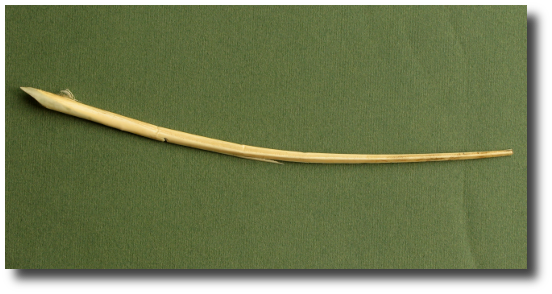

Each material that was written on required the use of different writing tools. On papyrus, a reed pen was used, whereas a stylus was the tool used for wax tablets. Parchment and paper required the use of quills. Until the XIX century, bird feathers were used, most frequently goose, which were suitably cut. They did not have containers for ink, like fountain pens today, so they were accompanied by ink-wells, and the scribe had to additionally possess a knife for cutting the quill as it easily became blunt. In the middle ages, ink was produced from various substances, including gall, vitriol, gum and vinegar, and normally was dark brown or black. The shade of the ink and how much it faded with time depended on the substances used for its production and their proportions.

Have you ever closed a book or notepad with a pen inside? Former scribes also did the same. In our Archives, we have come across two such forgetful writers. The first lived in the XVI century, and left his pen inside the cards of the Krakow Town Records of 1592.

The second one forget to take his pen from the cards of a book he wrote in the XIX century.

In this way, thanks to the absent-mindedness of the writers, both goose quills, enclosed between cards of books, have remained until our times.

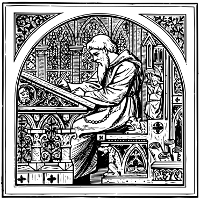

III. A scribe

Even in ancient times, there was the profession of scribe dealing with the rewriting of texts. In the middle ages (until more or less the XII century), the production of hand written documents took place within the walls of monasteries. In a specially designated room, the so-called scriptorium, work connected with creating codices was performed by monks, designated by the abbot. They specialized in various fields, depending on their skills and experience. Among the personnel of the scriptorium were calligraphers – experienced and learned in their art, ordinary copiers – novices learning the field of rewriting texts, as well as monks dealing with the decoration of books – miniaturists, illuminators and rubricators.

Miniaturists created book decorations, mainly compositions of figures, rich and developed, which generally consisted of many elements. The illuminator painted less demanding elements – initials and margin decorations. The rubricator was responsible for writing selected fragments of text with ink of a different colour, mainly red (the Latin word rubricare means “paint red”). In this way, defined places in texts were highlighted. See more about the art of decorating manuscripts in the section Adornment [4].

In later periods (in Poland at the beginning of the XV century) professional scribes began to appear. These earned a living by rewriting texts, however, due to the increased popularity of printing, they did not acquire a significant position.

Scribes were present in the courts of the rulers (in ducal and royal clerical offices), in cathedrals and collegiate churches, and around powerful clerics and secular people. Initially, they came from the clergy, and later they were also laity.

The following were connected with supreme clerical offices: the chancellor who headed it and sub-chancellors, secretaries, notaries, writers and auxiliary personnel – scribes.

Writers also carried out activities in town clerical offices – offices dealing with the keeping of documentation connected with the activities of the local governors. The number and education of the personnel in the clerical office depended on the wealth and needs of the town.

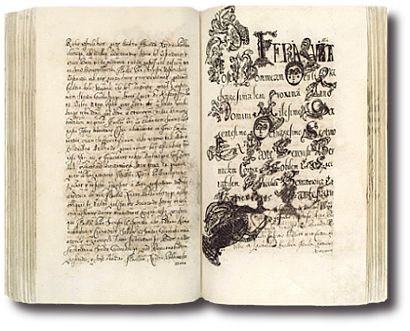

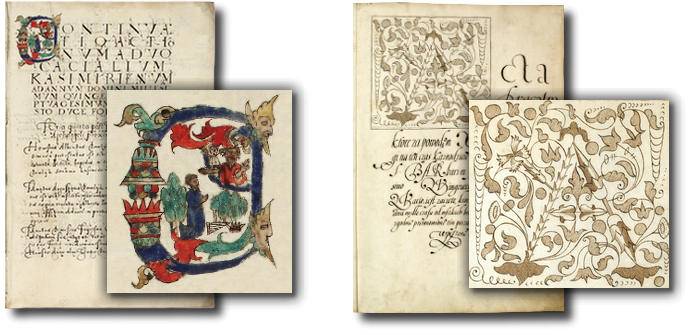

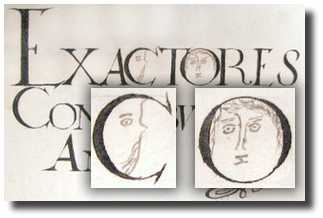

Ordinary scribes seldom showed off their artistic talent (perhaps due to a lack of time connected with the significant amount of work related to town organs). However, among town records it is possible to find ones where the writer, simultaneously fulfilling the role of illustrator, and sometimes miniaturist, carried out decorations with his quill, in the form of whole drawings or, much more frequently – single initials, headings, or fantastic brackets.

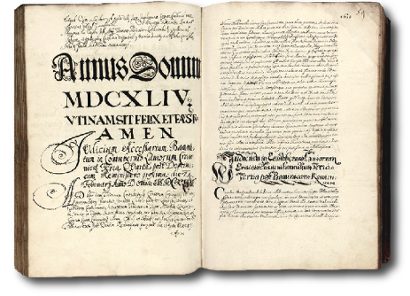

On the whole, writers were anonymous, however, there were some cases where the writer left his “signature”. At the end of the finished manuscript, they left notes (the so-called colophon), in which, beside the date of finishing the book, they also wrote their names, and sometimes functions.

IV. Adornment

Decorative initials, developed decorations of margins, distinguishing graphic capitals, as well as other decorative elements and compositions appearing in manuscripts had a few basic functions.

First of all – they represented adornments. The term illumination (understood as the decoration of initials and margins) comes from the Latin verb illuminare, meaning lighting, adornment. The beautiful appearance of a document was not, however, the principal goal in itself. Above all, it accented the rank of the manuscript and the prestige of its publisher (and also often the position of the recipient).

Therefore, while decorating manuscripts, gold was often used to illuminate the text in the form of thin flakes, e.g. for initials, capitals or miniatures.

Decorative elements also fulfilled a function – they helped readers to find orientation in texts. Thanks to the decorative letters, capitals, or whole pages, distinguished from the remaining parts of the text, the reader could more easily find its particular parts (proof of this could be examples of capitals decorated with such style and generosity that... their reading could be hindered).

Planning of the location of decorative elements in manuscripts took place at the beginning of the “design” process.

The scribe, whose task was to write down the principal parts of the document or book, left empty spaces in the places designated for the decorations while writing the text.

He did the same – illustrated by the example placed beside – with reference to the planned initial, which for unknown reasons was never finished. However, thanks to this example, among others, we know how work on the composition of a manuscript was organized.

designated for an initial.

A large role in the decoration of manuscripts was played by specialized illuminators (see A scribe [3]), however, the work of the scribe was also significant.

The style of writing itself and the way of writing down text by the writer – with due care and according to the principles of calligraphy, led to order and harmony in the whole manuscript. After all, in the case of produced books e.g. related to the activity of courts or town rulers, created due to the activity of such organs, on a larger scale, the role of the illuminator was filled by writers, carrying out decorations with quills.

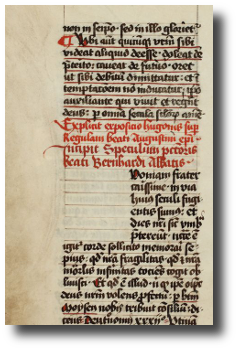

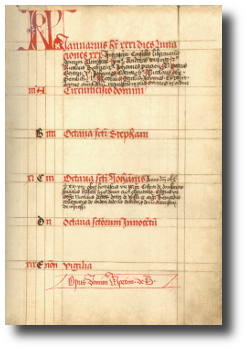

The simplest form of adornment in manuscripts was to distinguish particular letters, expressions or fragments of texts. This was carried out, for example, by writing parts of text with a different colour ink than in the remaining parts.

The most popular was to use red paint, in other words, rubrication (the Latin word rubrica means red paint). That's how rubrics were created, in other words, fragments of text written in red.

They were used mainly for headings, fulfilling, thanks to their colourful distinction, the function of tagging a selected place in the text.

To ease orientation in the text, there were other distinguishing elements placed in manuscripts – different from the main text due to their shape or size, among others.

These were initials, decorative capitals, decorations in margins and miniatures.

These elements were, on the whole, much larger than the main text of a document, and distinguished specific places in the manuscript by drawing the attention of the reader. They simultaneously fulfilled a decorative function and, depending on the size and wealth of the ornaments, they emphasized the importance of the manuscript.

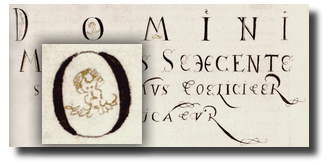

An initial, in other words, a letter beginning a paragraph of text, was written in a defined field, whose shape and size varied. They could be included e.g. in an oval form, or a rectangular one. The initial was most frequently written in a significantly larger size than the text (sometimes it even took up a large part of the page). It also often differed from the rest of the text in colour.

In the area of the initial, various types of decorations were painted – human forms, or genre scenes (the so-called figurated initial) or it was filled with plant and animal motifs or geometrical patterns (the so-called ornamental initial).

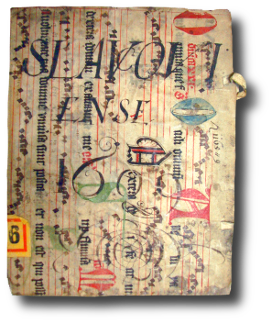

Not only were single initials decorated, but also whole words, headings, and even paragraphs of text.

Decorative writing was used for this, and was larger than the other letters, and often also different from the rest in its style.

Besides this, such headings were often decorated with additional elements – depending on the skill and inventiveness of the creator – from simple drawings to complicated beautiful ornaments.

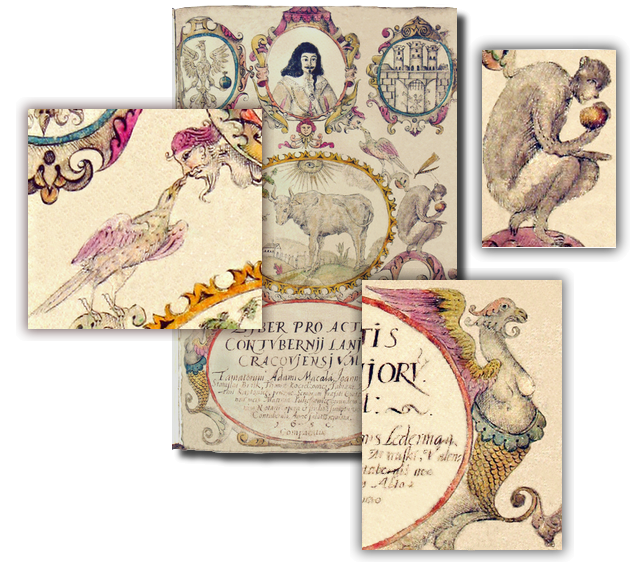

Decorative elements were also placed in the margins of manuscripts. These were often paintings of colourful, dynamic graphic compositions. The subjects of these decorations varied. Generally, they were plants, flagella and garlands consisting of leaves, stems, fruits and flowers. We define this type of decoration with the name foliage. Foliage was also sometimes additionally enriched with drawings of birds and animals.

A complement to foliage were also the, popular especially in the middle ages, so-called drolleries (from the French word drôlerie, meaning comical scenes). These were fantasy motifs, presenting people and animals (often imaginary ones), in comical, unreal or grotesque forms, or whole scenes maintained in the same convention, both from life and from the world of fairy tales.

It is also possible to find borders in preserved manuscripts. This is a form of margin decoration, made on all the margins of the page – just like a kind of frame. It could contain figurated decorations and ornaments, which may repeat (e.g. symmetrical, on opposite margins).

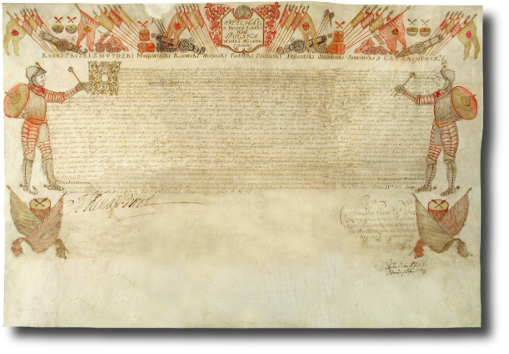

Decorative elements sometimes played the role of graphic commentary to the contents of the manuscript. One example here is heraldic motifs, drawings of weapons and arms (the so-called panoply), or elements appearing “on occasions”.

decorating the property acquisition deed for Grzegorz Kazimierz Podbereski,

subject to obligatory military service by him and his male offspring.

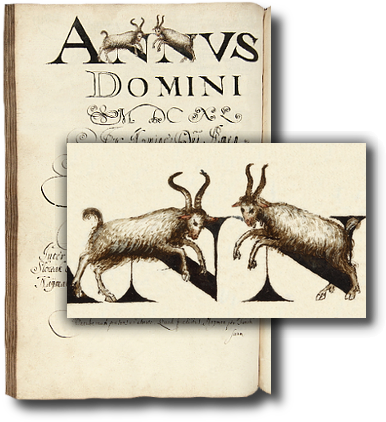

painted in the heading beginning the entries for the year 1640.

A symbolic presentation of saying farewell to the old and welcoming the new year?

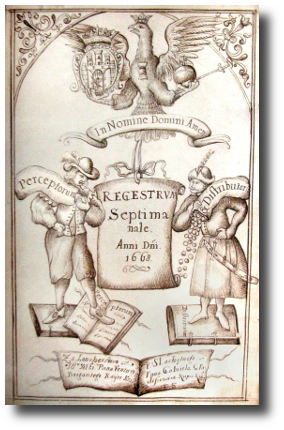

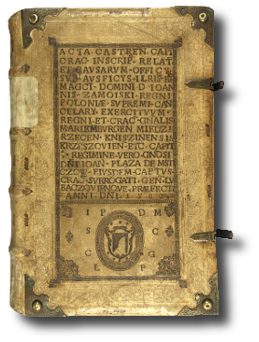

The title pages of books and volumes were decorated. Besides the title of the manuscript itself, which was generally written in decorative writing, plant and animal motifs were placed on the title pages, as were symbols and coats of arms, drawings relating to the contents of the books or ones that were totally unrelated. All depending on the inventiveness and fantasy of the creators.

of the town of Krakow placed on the title page of the Record

of Income and Expenses of the Town of Krakow from 1668.

Relatively often, especially in manuscripts with a more usable character (for example, in town records), drawings and decorations testifying to the sense of humour of the writer could be found.

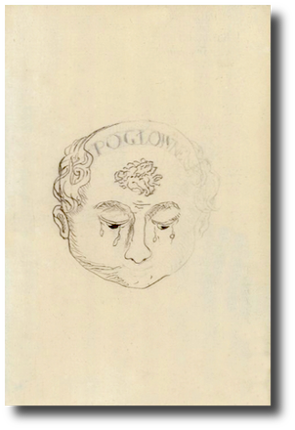

This tax was known as 'poll tax' and was collected from each resident of the town (“from each head”),

regardless of wealth or income. The writer showed a large dose of empathy towards the tax-payers

oppressed by the tax collectors, drawing in the book a crying head with the description “Poll tax” on the forehead.

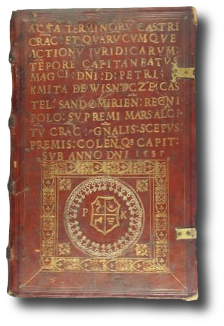

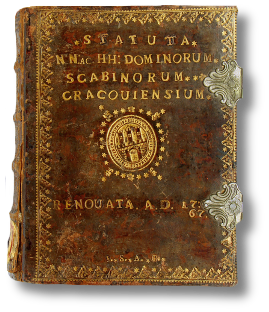

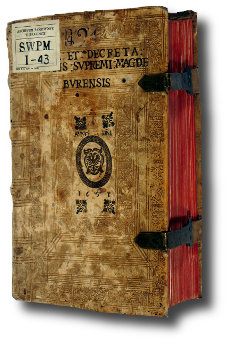

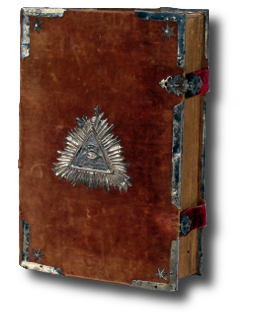

V. Covers

Due to the lack of durability of the materials, on which information was recorded, that is, parchment and paper (decidedly more brittle in comparison with stone or metal previously used), particular care was taken to safeguard the created manuscript.

It was stored, depending on its form, in tubes, cases, or boxes, and after books became more popular – it was additionally protected with a cover.

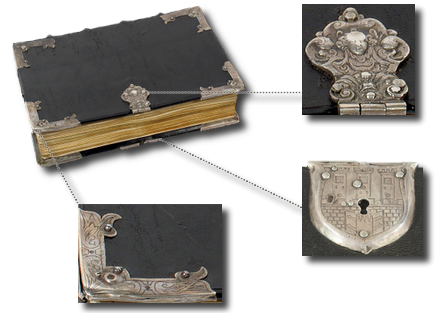

In Europe, in the early middle ages, valuable codices were given expensive covers. They were made from sheets of noble metals, gold or silver, or decorated with valuable plates, including ivory ones. Encrusted, glazed, with embedded precious and semi-precious gemstones, it represented an artful piece of jewellery. Such heavy covers, created using goldsmithing techniques, were a wonderful safeguard against the potential deformation of books.

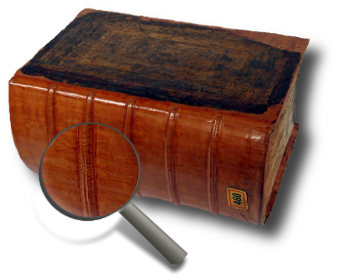

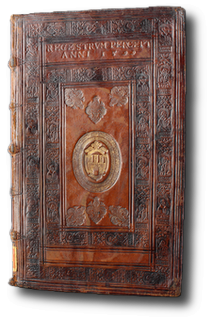

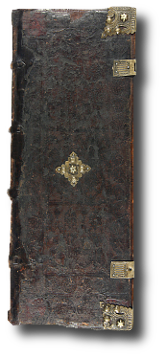

Manuscripts which were less “ceremonial”, designed for use, were bound in leather, which in Poland was used for such purposes from the XV century. Together with the increased popularity of this type of binding, goldsmiths moved into the background, and the greatest area for presenting their skills was obtained by book-binders.

Book-binders (the main centre of book-binding was located until the XVII century in Krakow) dealt with connecting pages inside books as well as creating and decorating covers, in cooperation with goldsmiths and blacksmiths.

After sewing the pages into quires and connecting the quires (helpful here were catchwords and signature marks – special designations of the correct page and order of quires), books were created.

Quires were sewn together in a few places using threads. In the place of the stitches, in order to reinforce them and prevent the threads from cutting the quire, a leather strip or laces were added. When sewing the quires, the threads were wound around these strips/laces. In this way, the so-called raised bands, thicker parts of the spine, were formed. These were especially characteristic of medieval covers. They are visible on the cover spine – in the form of horizontal swellings in the place of the stitches of the quires.

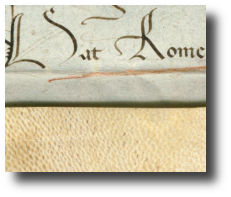

In order to stiffen the manuscript, on the paper lining (front and back page of the covers) of such a created book, parchment, ordinary leather or fabric was glued.

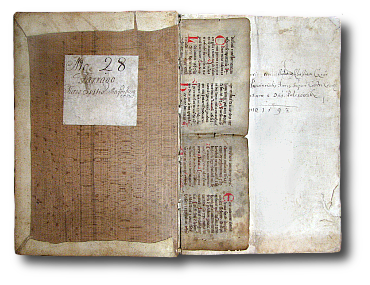

Parchment used for covers often came from old books. The use of pages obtained from old manuscripts was widely practised, due to the cost of parchment (today, some historians are conducting research exclusively into such covers).

With larger, and therefore heavier manuscripts, linings were combined with boards (where the Polish saying of “to read a book from board to board” comes from), which was then covered with leather or fabric (e.g. velvet or satin), and later also with paper.

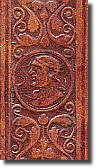

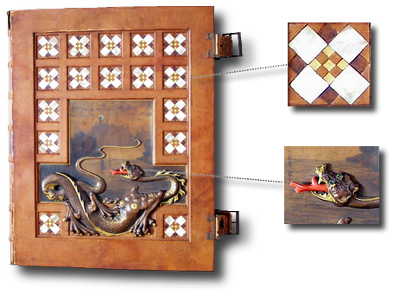

Leather (pig leather was mainly used for covers) was often decoratively engraved. For this purpose, book-binders used single stamps and presses (wooden and metal), and later also cylindrical presses thanks to which it was possible to press the same adornment quickly and seamlessly, e.g. in the form of a decorative strip. In order to engrave one decorative composition, a large press was used – a plaque, which when printed on a small cover represented a complete, “ready” decoration, and in larger covers could be one of the decorative elements.

The composition itself and the system of stamps depended on the invention of the book-binder.

Decorative borders, subtle motives, religious images, figures from mythology and allegorical ones, portraits of leaders and philosophers. Such covers are often small works of art, captivating with their wealth of decorative designs and the beauty of the ornaments. The book-binders who created them deserve the title of artist much more than the description of “craftsman”.

Covers were also pressed with gold, additionally enhancing the beauty of the decorations.

With the objective of protecting the decorations against rubbing, as well as protecting the books themselves against damage, metal elements were placed on the cover (in this area the book-binder cooperated closely with blacksmiths), such as corners, borders, strips, metal sheets, or other fittings.

In order to prevent the deformation of books and cards, covers were also given metal buckles, often with leather straps.

Such fasteners eased the closing of the books and helped to maintain the block of the book in its original, non-deformed shape.

All of these metal elements of the covers, very often subtly engraved, with intricate shapes, apart from their usefulness, also had an additional function – they were beautiful decorations of the manuscript.

In later periods, it became popular to use covers in the so-called half-bound style – the spines and corners of books were leather, and covers were made of paper or linen and paper covers. Metal buckles fastening together books were replaced by string.

In special cases, in order to make the covers more beautiful, books were given to goldsmiths or enamellists, who complemented the covers with additional elements.

This custom also continued in later periods (XIX-XX centuries), when rich covers were given to important documents and books.

VI. Forgery

Documents were of great importance in public life, they were evidence in legal proceedings, and represented confirmation of defined laws, or facts.

The greatest authority was enjoyed by royal, government or church documents, however, private documents, used in various matters (e.g. to confirm financial obligations) were also of significance.

The strong position of documents and the faith in their “power” meant that counterfeiting appeared (in Poland from the XIII century).

A document could be forged in a few ways.

The first one consisted of preparing a complete forgery from scratch, with contents unrelated to reality or not in accordance with the intention of the real issuer of the document. The document also contained an unauthentic seal or an original seal from another document, which gave the forgery even greater credibility.

Another way was to “falsify” an existing document, in other words, to make some changes to it. These changes consisted of writing new words or symbols in clear spaces, or replacing a selected word or whole fragment of text with a different entry. In this second case, first of all, the place in the document in which the entry was to be changed was erased. This involved scratching the original text using a sharp tool (most frequently this was a special writer's knife). The scratched place was then wiped and smoothed with a crayon or pumice stone. The false contents were then written into such a prepared “empty” area.

Testing the authenticity of documents submitted in the court was conducted by the personnel of the court clerical office. There were also special instructions concerning the discovery of forgeries. Above all, it was analysed if there was a seal on the document and whether it was damaged or not. If the document was regarded as unbelievable, the parchment was cut and the seal broken, preventing its further usage.

Forgery was harshly punished, in 1400 in Krakow, one local resident was sentenced to the death penalty by burning at the stake after being convicted of forgery.

With passing time, together with the development of the state and the growth in the production of documents, forms of documents helping in the fight against forgeries became popular. Civil and court registers, in which entries concerning conducted cases were made, became more widespread. In the beginning, they were short clerical notes, which evolved into pages full of entries (referring to the whole content of the document). Books obtained the virtue of public office. From the entries in them, the so-called extracts were issued, whose receipt was much cheaper and faster than obtaining the documents in a traditional form. Of course, the were also forgeries of the issued extracts, however, these forgeries were much easier to verify because they could simply be compared with the entry in the book.

Current methods for testing the authenticity of historical documents to some extent resemble an action film – the “investigation” focuses on a wide-ranging analysis of parchment/paper, the ink used, the wax used in the seal and, above all, the construction of the document, language and style of writing. To reveal former forgeries, it is also useful to have palaeographic knowledge. Tests must be, however, conducted in a wider context, with familiarity of the environment in which the document was prepared and the realities of the era.